The Mottini family and the Beppin cousins.

Achille Compagnoni and the four brothers.

Thoeni's dad, Don Parenti and the Longa family.

Engineer Pellentz and the Sartorelli family.

To write a story, you should always start by defining its characters, and when you want to tell a one that is one-hundred years old, the candidates are plenty, and someone always ends up outside the frame.

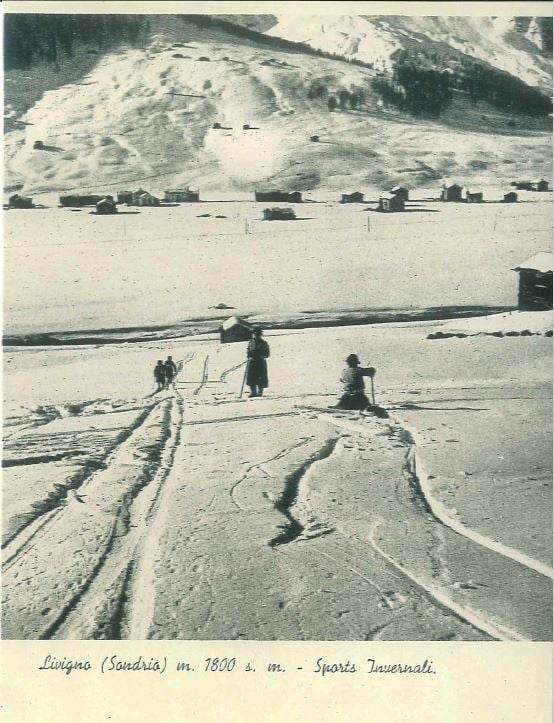

There was nothing here.

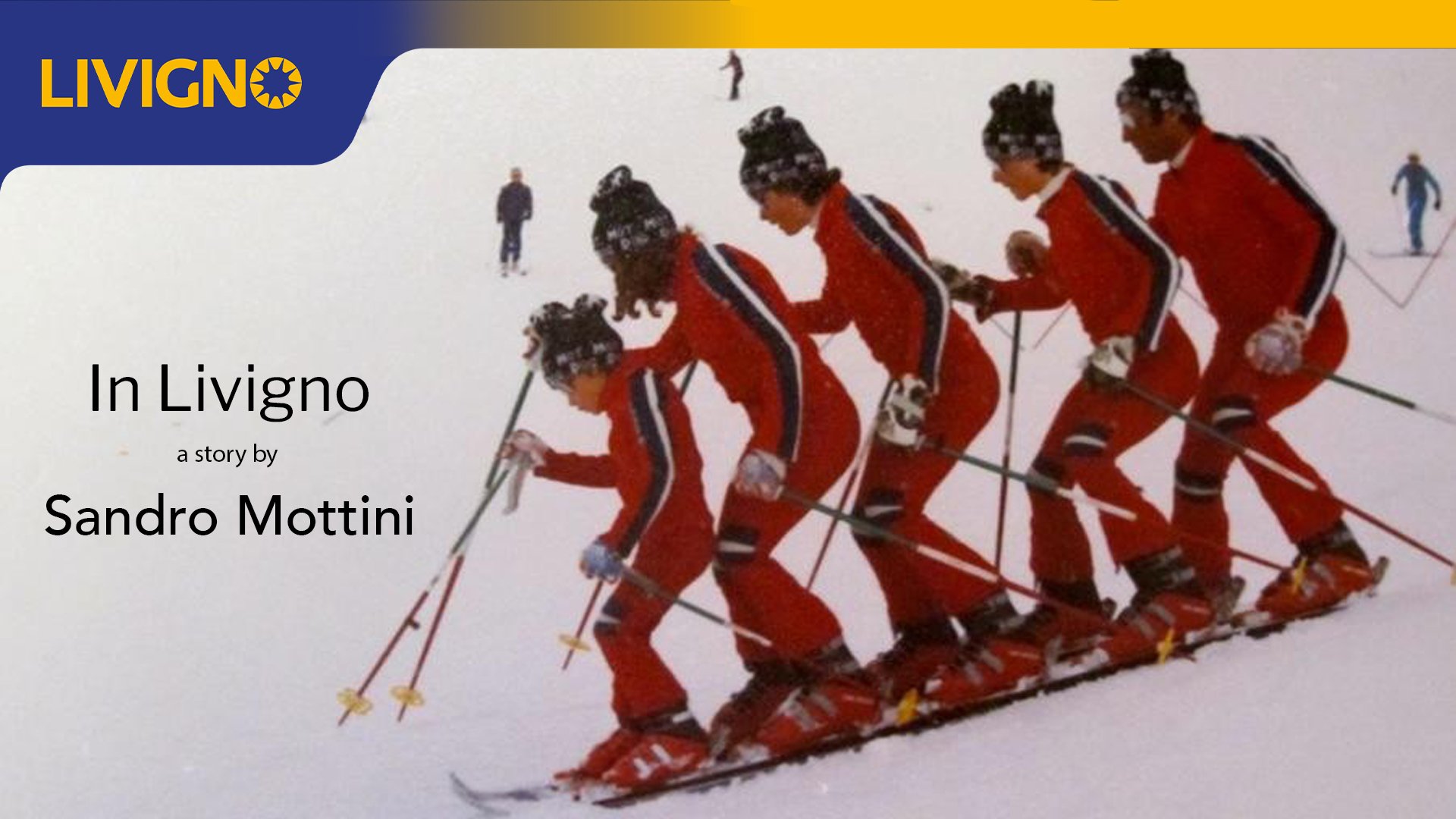

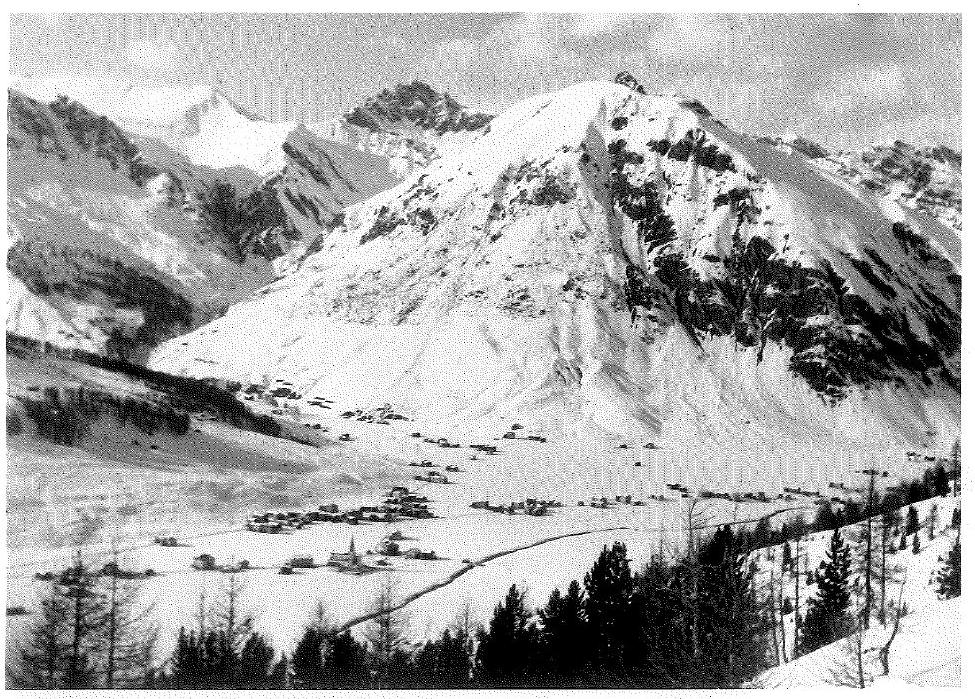

At the beginning of the last century, there was nothing in Livigno.

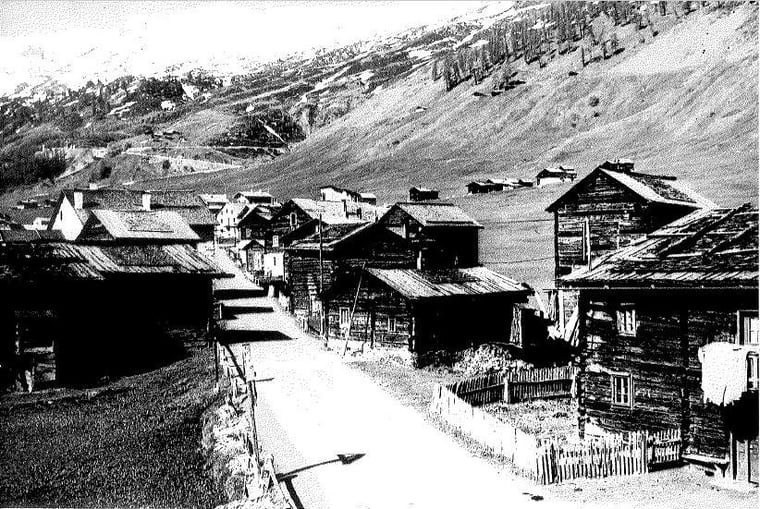

Only one thousand and two hundred souls lived here, struggling against the mountains and its edges, especially in winter. The days were marked only by the will of nature, and the passing of time, and everything that men could decide - such as the name of the streets - ended up reflecting the though, hands-on essence of a harsh era. Via Ostaria, via dela Gesa, via dela Fontana.

By mid-1920s, after the Italian army finally tamed the Foscagno and opened up the pass that would connect us to the rest of Italy, all of almost all the able men in town went to Switzerland, in St. Moritz, to prepare for the 1928 Olympic Games.

The Waldhaus, the Grand Hotel, the Kulm: all the great hotels destined to change the face of the city, and become a symbol of the power of local aristocracy, were brought up by Livigno arms, who never could have imagined the value of such experience. A value that, one hundred years later, we do understand, now that Olympia is so close.

In any case, in the lethargy of those cold decades, those between the two Great Wars, there were also those who tried to wake up our population, shaking it from the sleep of its millenarian peasant habits. Like Don Parenti, a magnificent daredevil from Brianza, lent to Christianity, who, for forty years, warmed up the valley, becoming a historical figure.

After having brilliantly passed the exam to become a lawyer, our hero heard the divine call, and decided to knock on the Ambrosiani's door to study theology. However, mad-headed as he was, Parenti did not fit in very well with the rigid formality of the Milanese order, and ended up moving to Como, to finish his studies and become a priest.

So, he was sent off to Trepalle, a town even less evolved than Livigno, and where a priest hadn't set foot for a ridiculous amount of time. The creaking and drafty parish house, was reopened for him and his mother, who accompanied him to that extreme border of the known World. Water dripping down the ceiling, when he asked if there was a faucet in the house, they told him water was at the stream, and not to worry, that the residents would go get it for him, everytime he needed it, because the people from Livigno may not have much, but they put their souls into it.

Then, he started thinking how to exploit the energy of such stream, and using the generator to light up the church and the parish house.

Don Parenti rose to the occasion, and despite saying that "they sent me to Trepalle as a punishment, and I will stay here as punishment", he was adopted by the entire town. Or maybe it was the other way around, and it was he who adopted the town. It doesn't matter. What is for sure, is that he brought here a new way of thinking, and it was not uncommon to see him wheezing by on his skis, with his tunic flapping, to pass the Sacraments in the most remote huts.

A few winters later, World War 2 Veterans - young men covered in mortar ashes - came back from the war with the need to live a new life, a fuller life, in the hope of discovering that there was more for each one of them, than misery and pain. So former and current Alpinists started opening up roads and creating tracks, to give a different, more humane, darker meaning to the passing of time.

There were no ski lifts then, but the Longa family had a small crawler they used to do anything, and every once in a while, when a job was done, they transformed it into a snowcat, by hooking a long rope, where we would hold on to climb with our skis.

The Germans were the first to look at our town with different eyes. Here too, details are lost in the memory of those who are no longer with us.

Luckily, I was there, and I'm still here.

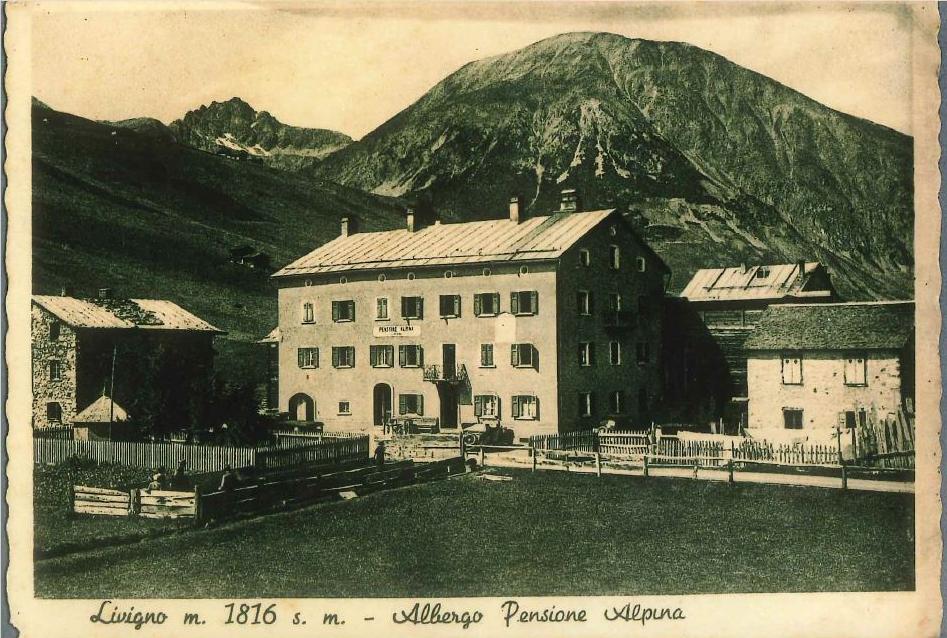

In those years, an enthusiastic group of tourists from Stuttgart, referred to by the highly respectable engineer Pellentz, started occupying all of Livigno's hotels, moving here for a month or so, server and revered in any possible way. Those were: the Livigno Hotel, the Bernina Hotel and the Alpina Hotel, which had been built by remodelling the old roadhouse.

Everything was done by letter. They booked them all, making an appointment with the hotel managers.

And then they set off from Germany.

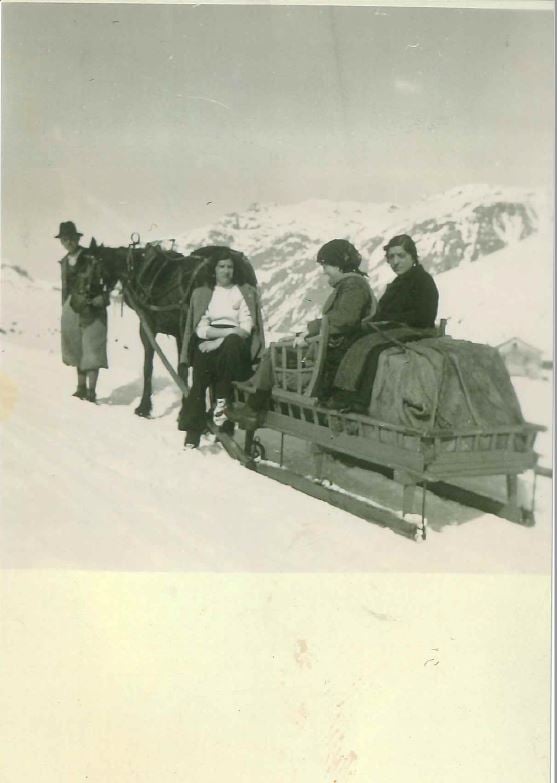

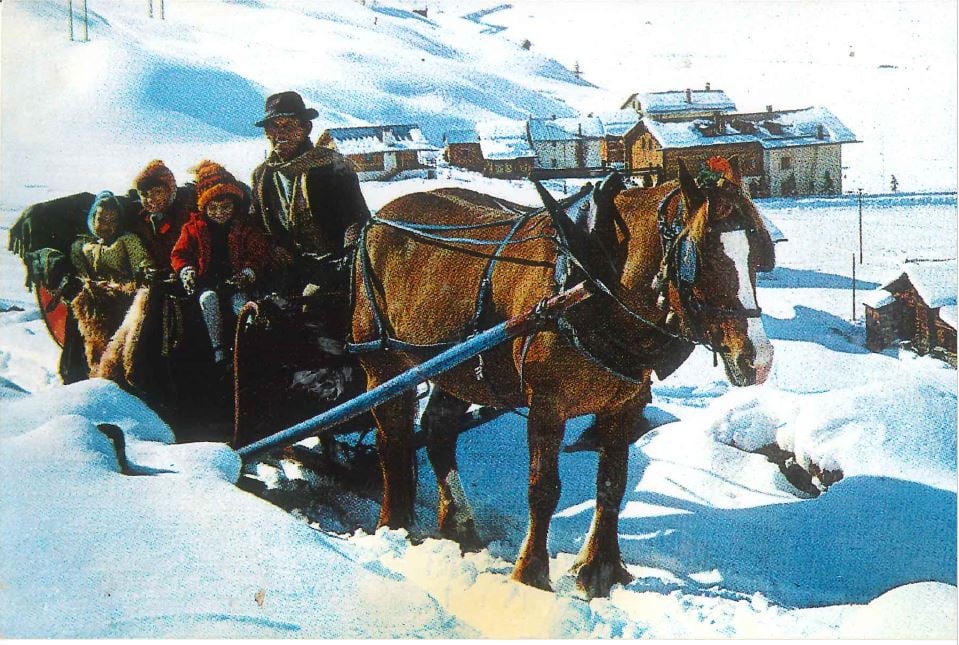

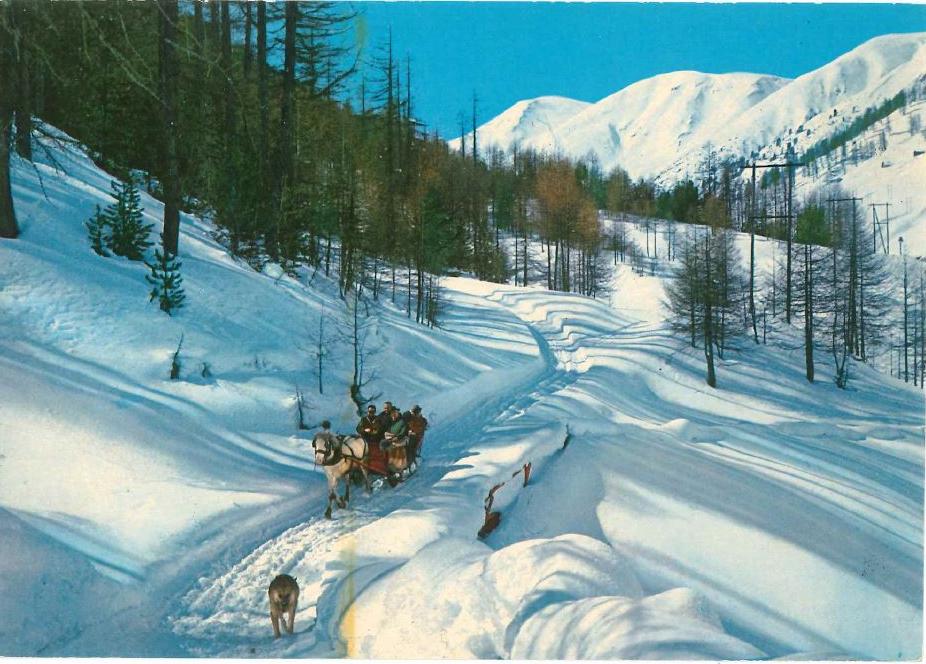

Train after train, exchange after exchange, they reached Zernez, and then continued with the Santa Maria post bus, until they reached the Drossa, on the Swiss border, wwhere our sledges were waiting for them after a journey of more than five hours.

Once in Livigno, they divided themselves in groups of ten people, each one of them accompanied by a guide. Sertorelli, Thöni, Peccedi, Cusini, Mottini: they changed destination every day. Went up with sealskin, and came down on virgin snow.

I was often included in this tussle, in the guide group, so to speak, even if I was only a scrawny kid, and even if the Engineer's Germans, in the end, knew a lot more than us. On anything, really.

My brother Benedetto and I grew up sharing a single pair of skis, and since none of us would ever ask the other to give up a snow-filled afternoon, we used one each, balancing our feet in single file.

I spent my days between family tasks: at dawn, I made bread, since we had a bakery, and in the evening, I served tables in our family hotel. Despite my very spare free time, I loved doing sports, and I launched myself down the slopes anytime I could.

However, my family "carried arthritis", as they used to say, and this legacy was ruining my life, when I was still young. I was still a teenager, when they made me wear a back brace underneath the work uniform. I remember, one day, there was a middle-aged man sitting at one of the restaurant tables, looking at me more closely than usual. He waited for the hall to empty, before asking me how come I was wearing a back brace, at such a young age.

He was a city orthopaedic, who recognized my stiff posture and told me I would better not fall for it. "Don't feel sorry for yourself. If you start with the back brace now, you'll never take it off. Throw it away, and when your back hurts, go out in the cold for a nice run, than lay down on the ground and clench your teeth, until the pain goes away. You'll have a long life!"

So I threw the back brace away, and started doing sports every day, and even if I had to get surgery on both my hips, I skied for over sixty years. A gift I owe solely to that man.

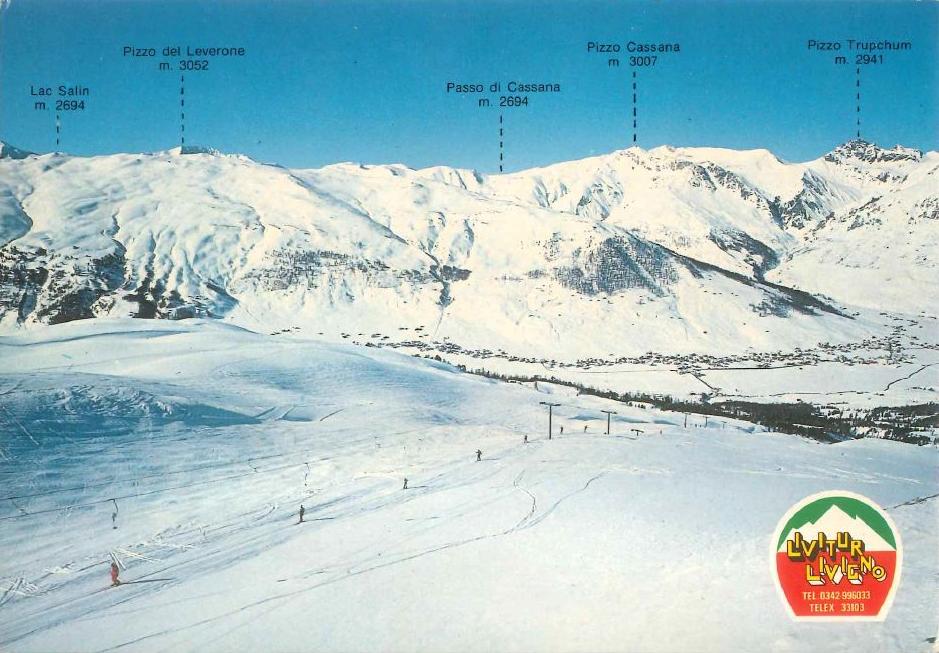

Livigno was growing, the echo of the war was getting farther and farther away, the Foscagno started opening up even in the winter, and, along with the pioneer tourists, the first ski lifts were built.

Valtellina was so remote and distant, that the railway between Sondrio and Tirano was not state-owned - as the Country did not care. It belonged to a local company. When finally the State took over the route, the FAV ( Società Anonima per le Ferrovie dell’Alta Valtellina), invested in chairlifts and lift systems, both in Livigno and in Santa Caterina, shaping the future that was waiting for us. The only thing missing were ski instructors, which were very few in the entire valley.

I was one of the first to try and get a license, which, at the time, was obtained: by proving that you had took part in some kind of good-level competition and ranked between the top five; by doing a three-year course; and then passing an exam, which I did on the blue ice of the Bondone Mountains, in the winter of 1962.

On that occasion, they set the exams at the end of the Interski, an international event during which the greatest minds of world skiing met to compare their way of teaching, and choose the best. There were Americans, Germans, Swiss and Austrian - all snow professors - and after witnessing their theoretical demonstrations, like noble lords, it finally came the time to earn my tiny instructor license.

During the night, it snowed like never before, and the examiners were forced to make us climb up the icy slabs used in speed skiing, in order to gain up enough speed and not end up stuck in five feet of fresh snow that had fallen on the track.

I was saved by my metal ski, which I decided to bring along, They were more flexible and sturdy, a technical wonder I was the first to import to Italy. For this reason too, when I crossed the finish line, I was greeted with a less than flattering, "There goes the smuggler", as one of the examiners cried out.

Since then, I've never stopped teaching, skiing and trying new things, following the incredible evolution our Town has experienced, step by step. We were the first to bring here hot-dogs, and then freestyles, which, better than anything, seems to embody Livigno's free and edgy soul.

When, in the rest of the World, they had the right tools to create the slopes, we built our humps with our arms and shovels, getting corns on our hands, to create the slopes of our dreams, modelled after those of the great American champions.

I lived over 50 years of adventures on the snow, of discoveries, innovations and follies, during which I experimented as much as possible, side by side with my town. We made five people ski on the same pair of skis at the same time, we made a dromedary ski, tried hundreds of different jumps and hit our buttocks at least twice the time. Without ever losing the spirit of the beginning, the spirit of Don Parenti and engineer Pellentz.

And if I think back to those Livigno residents who, one hundred years ago, set off to go to the sparkling St. Moritz and build luxury hotels for the 1928 Olympics, I would like to talk to them for just a minute, and tell them that, even if they don't know it, that time was essential, because it marked the beginning of a century-old journey, which will end up with the Olympic Games coming to Livigno.

Livigno, where there was nothing, one hundred years ago.

Livigno, where there is everything, today.