I've always been the baby of the house, the last of the breed.

The outnumbered third son, born seven and ten years after my sisters. And I turned being at the back of the line into a lifestyle.

Since I was a child.

Stray to the core, desperate enough, always curious, my favourite game was being outside, sneaking out of the house as soon as school was over, and getting back at sunset, covered in snow, earth or who knows what else.

They were the 1980s, there were no cellphones, and when a child went out to conquer the town, mothers and fathers couldn't do anything else but wait for them, hoping they would get back all in one piece, without racking up too much damage.

I liked to play with wood, and build makeshift shelters in the woods or in fields. I liked to take my out-of-towner friends - those who came here for the summer and stayed all season - out to explore. I liked to watch construction sites, and bother workers into telling me how things were built.

In those years, Livigno was very much different than today. But Livigno people weren't.

The town soul has always stayed true to itself, to its mountains and to the snow, which is a piece of us, something we are always looking for, even in summer, as if we couldn't live without it.

I remember that, as soon as I woke up, I ran to watch the buses leave at dawn, headed toward the Diavolozza, to sky on the glacier, and I dreamed to get on them too, to see how the snow in July is.

But I had to wait for winter, or, at best, trick time grass skiing.

I had just started out with ice hockey, and it was amazing, especially for the team we had built. Adults and less so, talented or not: that team made me feel a part of something important, bigger than me. It's a dynamic, complete and identity-building sport, because it forces you to move all the time together, like an orchestra, like the town band, where everyone chips in, in their own way.

Then the sports club closed, and I switched to something else, but I am happy to know that someone is bringing this sport back to the valley, because it should not be missing, in a place like this.

I took off the ice skates and put on the skis.

Even though, in the end, I was born and raised on skis, just like everyone else here. I was already "mad", so, for good measure, I always took the crown as the most reckless of the team, even on snow. If something was not allowed, you could be sure I would be the first to break the rule, proud of my stubborn head.

You couldn't jump down the chairlift while it was moving, and I invariably did it. Every year, they took my card away at least three times, only to be pitied by my puppy-dog eyes and give it back, making me promise that I "really won't do it, ever again".

And even though it took a couple of decades, in the end I kept my word, and I began abiding by all the rules, even though my generation's plant operators never miss a chance to remind me of my shenanigans.

By growing up in Livigno, with such a temperament, it is no wonder that my passion was freestyle, and it still is, since I believe that we will be faithful companions until the end of my days.

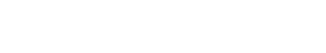

I looked at older boys and tried to imitate them, between tricks and somersaults.

When you are a child, there is no fear, because it hides itself perfectly under the cloak of infantile recklessness, dangling from adrenaline's mouth.

Then you hit your butt once or twice, and you think again a little.

You took a couple of hits, spent ten days away from the skis - just like the repentance the priest gave you when you said something bad at confession - and got back on the slope with a tiny little bit more respect.

Respect that infaillably disappeared on the first jump.

To me, freestyle always meant bumps and moguls, and this sport charmed my eyes and my heart in leas than five minutes. There is something strange, counter-intuitive, almost, worthy of a contrarian like me, in artificially creating obstacles to separate the peak from the valley floor, and making the descent more complicated and gnarly.

I still think about the reason for the bumps, even now that my back is not what it used to be, and maybe there is no right answer. Or rather, there is, but it answers a different question.

Yes, I would do it again.

I would start anew and devote myself to moguls, again.

As curios as it may seem, that is the most amazing thing there is, so I would do it again. Not in the same way, maybe, but I would do it again. A mind and body challenge that defined my entire life.

You must be a top athlete, flexible and strong, at all times, to domesticate the bumps.

You must fight for your focus, which should be indulged, not followed, otherwise you are always a chord late with respect to the slope music.

There are long and short ones: this is an arrhythmic and asymmetrical sport, and the speed you tackle it at is always too fast to evaluate them one by one. The eyes can't take it,

they remain fixed on the horizon, while the feet and the skis assess the texture and shape of the heap of snow beneath you, in real time.

It's a dance with the slope, a stroke, a dialogue, that suddenly erupts into a leap toward the ski. It's like a first date, that, after a zigzag of chats and glances, ends up with fireworks, between the sheets.

First of all, I was an athlete.

A little bit of World Cup, and a lot of European Cup, where I often ranked between the first 10, even though there wasn't that much attention on this sport.

We were over 100, at the gate, every race, and I did my best to steal the secrets from the best athletes, and improve myself as much as possible, also because the money to travel would often come out directly from my pockets, and I couldn't waste a single cent. Then, at the very best moment, the military service came, and, between one January and the next, I lost almost two years.

Our minds are strange beasts, and when I resumed the races, despite the body not being that much different than a couple of years earlier, I struggled to get into a wretched top 30.

"You ace it in training!", was my coaches' best line, who struggled to understand why I suffered the tension so much, when the key moment came. It was an actual block, and I was never able to overcome it, just like a trampoline. It stayed with me for my entire career, even when, after a strenuous climb, I managed to get back to the World Cup a couple of times.

Ours were handmade humps, maybe the last one to be built by skis and careful shovelfuls. It took days to prepare a slope for a race.

We set the poles in single file, and then we skied on them, descent after descent, like in any slalom, letting the athletes' edges and blades dig in the grooves to create the bumps. Then, with a lot of patience and effort, we would finish them off one by one, with a shovel. Not exactly an easy feat.

So, when I stopped skiing, given my great passion, I decided to get behind the wheel of a snowcat and find a way to build a track faster. Nobody took me seriously at first, but I perfected my technique, with wit and hard work, to reduce the required times down to a minimum, and complete the slopes within a couple of days, which is not too bad.

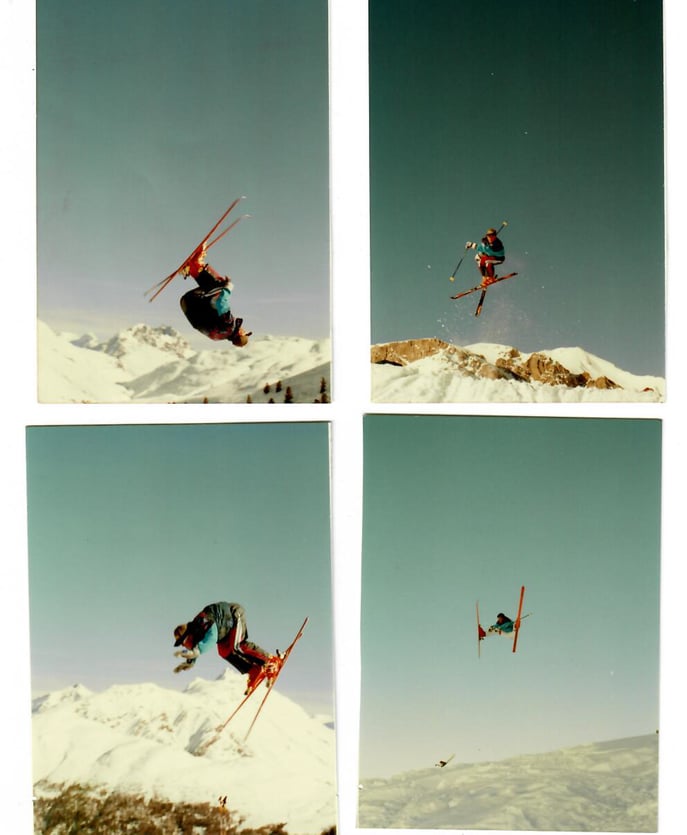

Then, the idea tickled those who did it for a living, and, almost without knowing how, I found myself preparing bumps and athletes for the 2006 Turin Olympics, the last edition of the Games in Italy, before the next one. It was a short step from Piedmont to the rest of the world, and for a few years I built my slopes and my moguls, around all the international circuits, even in those places I used to dream about, when I was a child, those with snow in the summer.

And today we are here, planning the next Five Circles appointment with the entire community, which will begin and flourish in the same fields and forests I used to play when I was little.

For me, this new beginning, was like going back to the future: a journey in time that reminded me - like it hadn't happened in a while - my passion for this unique, beautiful sport, which has always been here, inside my bones.

The dream is convincing some young athlete from Livigno of the beauty of those bumps, and maybe take them to the Olympic gates, along with the rest of the town. And if this does not happen, it doesn't matter, because the experience of one person, however amazing, could end up forgotten, growing mouldy in an attic.

What's left is the culture.

A culture that, twenty years after Turin, should be capable of supporting the burden of history and the expectations of next generations. This means perfect slopes. It means dazzling organization. And also opportunities for the future.

It means taking freestyle in all its form and turn it into the day-to-day routine of our resorts, by imagining spaces and slopes devoted to its many faces.

It means building a future based on the identity of our Country, and when, after another twenty years, the Olympics will come back, we will have plenty of choice, because there will be many national talents to root for.