Italian kids love to play football.

It's our national sport.

It's part of our culture.

It's the first tool we have to socialize with other people.

Two backpacks as goal post, a supertele ball with its unpredictable trajectories (or a tango ball at best, which is heavier and flies less), a handful of friends... and there you go.

This applies to almost everyone; however, my story, my career and my life originate within the folds of that “almost”.

I grew up in San Rocco di Marano, a small rural outpost in Valpolicella, hidden between Veneto's hills, far away from the sea, and far away from the mountains, not too much though, since nothing in our Country is truly that far.

500 meters above the sea level, more or less, around 80 families in total, and just over 200 people - a clustered, intimate community, where last names are never used.

Well, then, to play football, more often than not, the town lacked the numbers, the people to make up two teams. And we had to find other ways to fill the time, and for my friends and I, the bike was our first choice.

Partly out of necessity, and party magical.

Partly a way of getting around, and party a way of life: my two wheels have always been my favourite place in the world, where I became a master of the road and of my own time, free as I was to go wherever I wanted, alone, minding my own business.

For an active kid, pushing on those pedals, crushing miles and miles in the narrow streets of that ancient town I was lucky to call my home, was the most effective way to entertain himself, a stress-relieving practice that calmed my anxiety and drained my energy reserves.

My mother said that, when it was time to ride my bike, I forgot about everything else, and I didn't even care about food.

The Owl Post x Livigno

Post recenti

I've always loved to tell a good story, and also to have many photos within reach, to reignite the memories featured in those stories.

If you think about it, it's funny how much narrative, how much storytelling there is in every single shot, and how all the film rolls of your life can become a jigsaw to pass down to others. Your photo albums say a lot about who you are, especially to yourself.

Every picture is a moment, and every moment a dot in the sky. If you connect them all, you'll see your personal constellation, the one that guided you right to this moment, and made you who you are today.

I've always been the baby of the house, the last of the breed.

The outnumbered third son, born seven and ten years after my sisters. And I turned being at the back of the line into a lifestyle.

Since I was a child.

Stray to the core, desperate enough, always curious, my favourite game was being outside, sneaking out of the house as soon as school was over, and getting back at sunset, covered in snow, earth or who knows what else.

They were the 1980s, there were no cellphones, and when a child went out to conquer the town, mothers and fathers couldn't do anything else but wait for them, hoping they would get back all in one piece, without racking up too much damage.

I liked to play with wood, and build makeshift shelters in the woods or in fields. I liked to take my out-of-towner friends - those who came here for the summer and stayed all season - out to explore. I liked to watch construction sites, and bother workers into telling me how things were built.

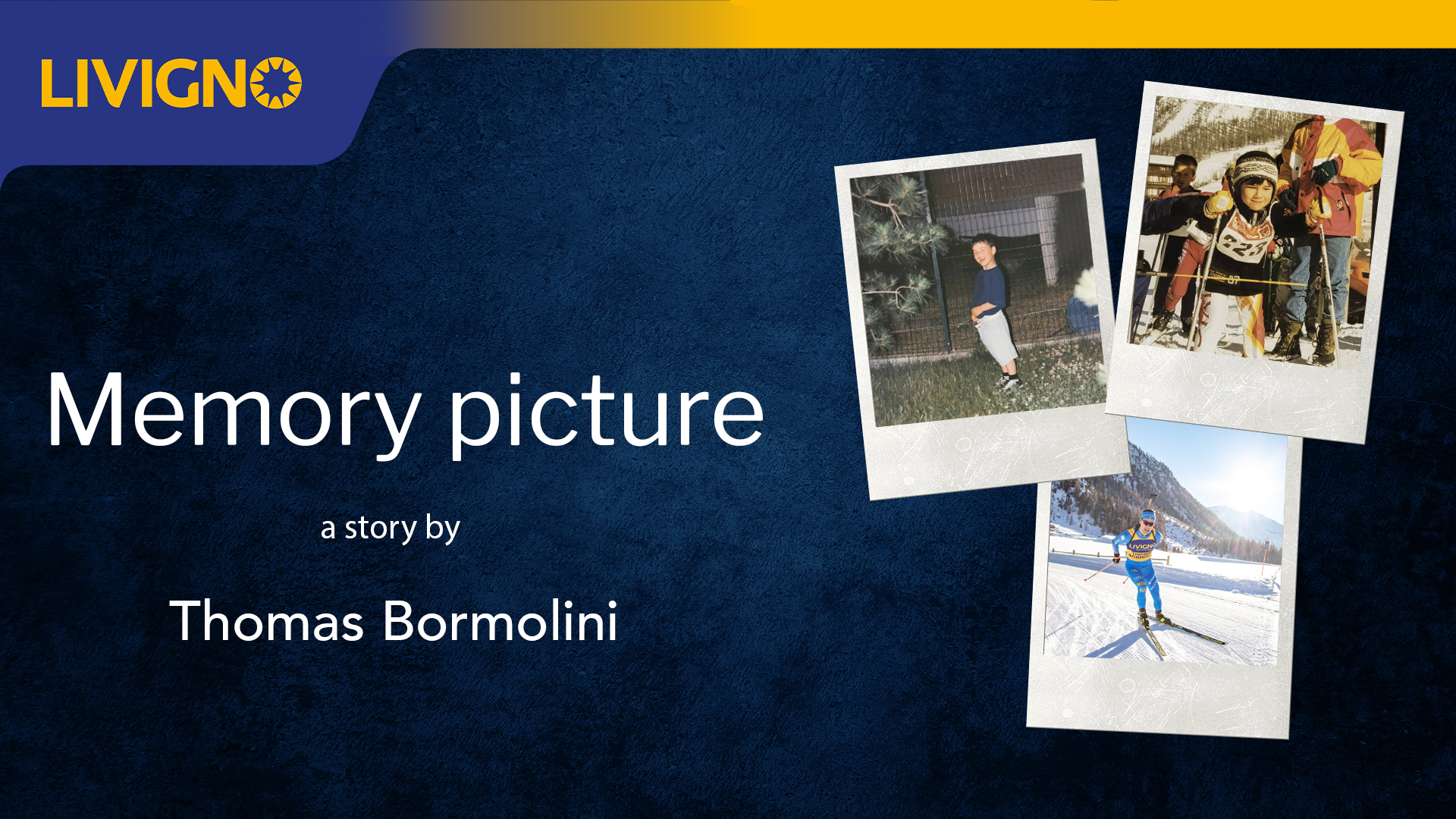

The Mottini family and the Beppin cousins.

Achille Compagnoni and the four brothers.

Thoeni's dad, Don Parenti and the Longa family.

Engineer Pellentz and the Sartorelli family.

To write a story, you should always start by defining its characters, and when you want to tell a one that is one-hundred years old, the candidates are plenty, and someone always ends up outside the frame.

The Olympics revolution always starts from the bottom up.

It starts at ground level and grows upwards, like a little brother who you watch grow one day at a time. Where I am now, on the far side of China, a short distance from Mongolia, there was nothing until a few years ago.

No structures.

No buildings.

No installations.

Nothing.

Just ice, the mountains and a small local community, that used mules to go up and down the paths and only had electricity until seven in the evening, before someone, somewhere, turned off the meters.